The Trademark Court Fight Between Chanel And Huawei

Background of the Case:

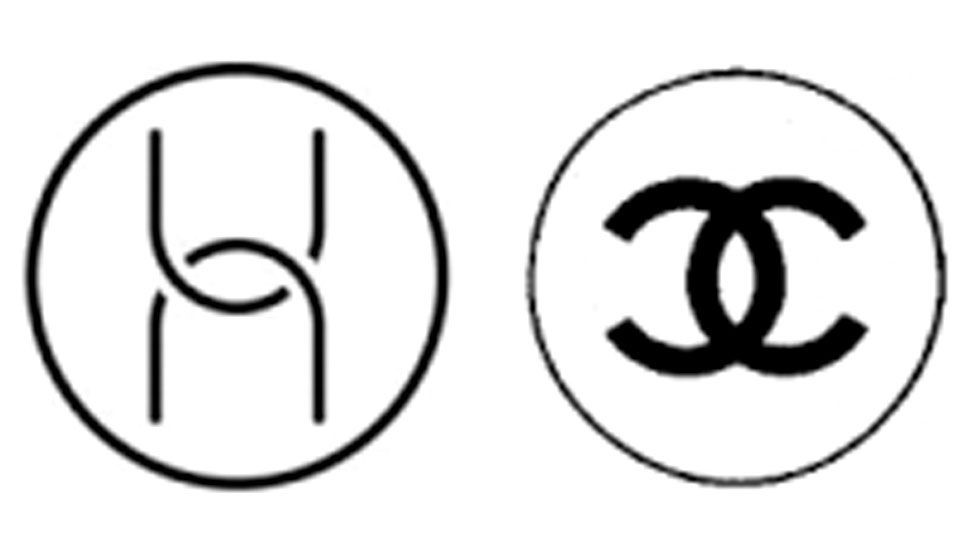

Chanel, a big name in the fashion world, recently lost a trademark infringement suit filed against a Chinese tech firm, Huawei, in the European Court. In 2017, Huawei filed an application with EU Intellectual Property Office with respect to Class 9 of the Nice Agreement concerning the International Classification of Goods and Services for the purposes of the registration of marks, for protecting its logo for ‘computer hardware, computer software and other related goods’. Chanel opposed the application because the logo filed for protection bears many similarities with its famous ‘two intertwining half rings’ logo already registered for various products such as clothes and cosmetics. This dispute exemplifies how luxury houses are incredibly possessive regarding their trademarks symbolizing opulence in the fashion world for people across the globe.

Detailed Analysis:

EUIPO dismissed Chanel’s opposition stating that the two marks were not similar. Secondly, it is improbable that any confusion is created in the public’s minds given the reputation and name that Chanel’s mark has earned over the years. Chanel’s appeal against the given decision was again dismissed by the General Court of the European Union.

According to Article 8(5) of Regulation No 207/2009, if there is a possibility that the newly applied for trademark may be able to take unfair advantage of the reputation of the brand which already exists, then to have broader protection, three conditions must be satisfied-

- the marks should be identical or similar.

- the mark seeking broader protection should have a name/reputation in the market.

- the mark applied for, if approved, should be detrimental to the mark which is already registered and should take unfair advantage of the same.

All these three conditions must be satisfied cumulatively, and if one of them is not followed, it will render the whole provision inapplicable.

Visual Comparison: The court held that the similarity between two marks should be assessed based on the form they are registered/ applied for without considering any remote use of their respective products in the market. After keen observation, the Court concluded that Huawei’s sign is “two inverted ‘u’s intersecting with each other to form a horizontal ellipse in the center”, while on the other hand, Chanel’s mark consists of “two ‘c’s which intersect with each other to form a vertical ellipse at the center”. The court suggested that there may be some similarities between the marks but they are significantly different as Chanel’s mark is curvier, thicker and horizontal, while the Huawei mark is less curvy and vertically positioned and the absence of a circle in the earlier mark and a consequent arrangement rules out any visual similarity.

Consumer Confusion: While talking about the confusion in customers’ minds or the public, the court said that since the court has already decided that the marks are not similar, it is not necessary to evaluate other factors as the question of confusion does not arise in the question first place. According to a case law1 presented by Chanel for achieving a broader protection under Article 8(5), it is not imperative to prove that if the mark is approved, it will create confusion in the minds of the relevant public concerning the existing trademark. The degree of similarity based on the visuals, phonetics or concept between the marks shall be considered sufficient to create confusion in the public’s minds. The court held that despite the similarities, like intersecting curves and the colour of the marks, the overall visual appeal of the marks is quite different.

Interestingly, there is no definition of ‘unfair advantage’ in law. However, in the Chevy case2, the Court explained that it could only happen when there is a likelihood that the relevant public may confuse the mark applied for with the trademark which already exists. It was also said that there has to be knowledge and reputation of the existing brand in the public’s minds. The Court’s holding is still very vague and broad, but it still gives a particular direction for deciding the definition of an unfair advantage. In Chanel’s case, the court held that reputation must be evaluated primarily based on the quantitative standard. Thus, the same will help calculate the possibility of an unfair advantage.

Chanel was also ordered to pay the costs for the unsuccessful party pleadings following the forms of order sought by EUIPO and the intervener.

Conclusion

It can be concluded through the court’s decision in this case that trademark only protects the actual potential use of the sign that is trademarked. Therefore, while comparing the similarities between the marks, one should see how or in what form they were registered. Any such use that is not mentioned in the application of registration shall be ignored. For example, Huawei has registered the mark in dispute for its Artificial Intelligence Life app for ‘smart homes’ while Chanel sells luxury fashion under its respective mark.

However, in the UK, under the tort of passing off3, the courts generally consider the potential of goods bearing a particular trademark being moved into a broader prospect of different range, i.e., the commercial reality rather than strictly confining the marks as they were registered.

For now, all that can be said is that Chanel is going to be vigilantly eyeing the actions of Huawei so that it doesn’t start offering/selling goods and services, which Chanel provides, under the disputed mark. The decision by the European Court is appealable before the European Court of Justice.